Colorado: Polarized by the politics of a rural-urban divide

At dusk on a June day, Columbine High School is empty. Sprinkler jets stream rainbows across the fading sunlight and bright green lawn. “Safety first” signs are taped on all the doors.

Fifteen years ago, English teacher Paula Reed thought something different might come from the deaths of 12 students and one teacher at the hands of two teenagers, that heightened awareness of gun violence would yield answers to the question of gun safety.

History has proven her wrong.

SIDEBARS

“It simply created a huge chasm, at least in terms of what we’re talking about as a nation,” she said. “What I see us talking about in the media and on social media is this hardline, ‘Guns are evil, we need to get rid of all of them and the NRA’s evil,’ and, ‘You can pry my gun out of my cold, dead hand; don’t come after my guns.’

“I think most of us are in the middle, but that’s not where the discussion is occurring. And because of that, we can’t have a sane discussion that results in sane solutions.”

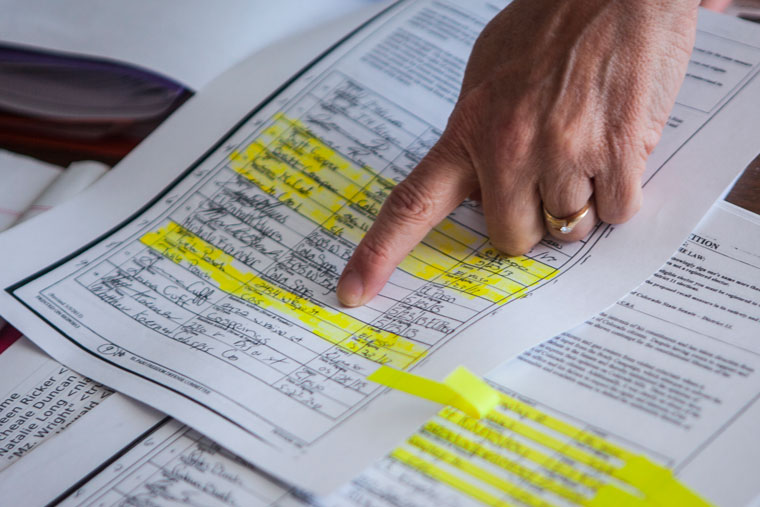

After the Aurora and Sandy Hook shootings, Colorado’s legislature ushered in unprecedented gun control laws, including universal background checks and a ban on high-capacity magazines. But gun rights activists fueled two historic senator recalls and a resignation. A group of sheriffs and gun industry stakeholders sued Gov. John Hickenlooper, who in June took a public step back from the laws he favored a year ago.

This is a state divided by two high-profile mass shootings that resulted in 27 deaths; between gun-rights supporters and gun-control advocates; by a set of laws that continues to inspire dissent among residents and lawmakers. As elections approach, conservative lobbyists and lawmakers plan to grab hold of public opposition toward gun control, find a path toward redder terrain and win back their firearms rights no matter how long it takes.

It’s unknown whether Hickenlooper will be safe in the state that gave President Barack Obama a 5 percent margin of victory in 2012. A Quinnipiac University poll released in July put him neck-and-neck with Republican challenger Bob Beauprez. And several legislative seats in traditionally more conservative districts will be up for grabs.

“We used to be a very Republican state, and then all of a sudden, I don’t know what happened, it changed,” said John Cooke, a sheriff in Weld County, Colorado, who was the lead plaintiff in the suit against the 2013 gun laws. “We need to do a better job of electing people to the Senate, the House and electing a better governor. And once that happens, I think a lot of these gun laws are going to be repealed.”

Eleven years ago, Colorado’s Republican-dominated legislature likely couldn’t have passed the gun control legislation that defines today’s debate.

Following the Columbine shooting in 1999, a bill in 2000 closed the loophole that allowed the two teenagers who committed the attacks to legally obtain their guns from a friend who bought them at a gun show. Between 2000 and 2013, Colorado only saw five gun-related bills pass, the most consequential of which barred felons and those convicted of domestic violence from possessing firearms.

English teacher Paula Reed stands outside Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo., on June 6, 2014. Reed fled the building with students during the shooting at the school 15 years prior. Having lost students she was close to, she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. Photo by Morgan Spiehs/News21.

“The gun issue … just wasn’t on my radar screen,” said John Straayer, a political science professor at Colorado State University who has observed the Legislature for more than 40 years. “I remember more contentious blockbuster issues having to do with mandating motorcycle helmets than having to do with guns until rather recently.”

In 2004, Democrats gained control of the entire Legislature, which they’ve held but for a brief stint in 2011 and 2012. And that Democrat-dominant culture, as well as a shift in the national narrative, was the impetus for major changes, Straayer said.

“State after state after state is trying to do something about (gun violence),” Straayer said. “What’s happening nationwide is happening in Colorado. The salience of the whole gun issue has stimulated the introduction of this kind of gun legislation.”

In early 2013, Colorado’s Legislature introduced Aurora- and Sandy Hook-inspired gun control measures that got the state talking about firearms. House Bill 1224 banned the sale and transfer of high-capacity ammunition magazines. Senate Bill 195 required concealed-carry permit applicants to take in-person training. House Bill 1229 required background checks for private gun sales and transfers, already standard for public sales, and mental health reporting to a federal database.

.

As the snow was melting to feed Colorado’s mountain streams, Hickenlooper signed the bills into law and Colorado made some of the most dramatic gun policy changes in the country. It came as the state also made same-sex civil unions legal, granted in-state tuition to Colorado high school graduates who immigrated to the U.S. illegally and improved voter access by supplying mail-in ballots for all active state voters.

“We did more than we have in the last 20 years in moving Colorado forward,” said former Sen. Angela Giron of Pueblo, who was ousted in one of the recalls.

Democrats have been able to increase funding, get better candidates to run and benefited from a shifting demographic. But Straayer said Republicans have contributed far more to Colorado’s leftward shift since the 1970s.

“The Republican Party, over a three-decade period of time, pretty much eliminated the moderates in the party and moved further and further to the right and made themselves less and less attractive to the moderate voter, to the swing voter, to the unaffiliated voter,” Straayer said.