Debate has changed since Newtown, but not always in predictable ways

Twenty months after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, some would say little has changed when it comes to guns in America.

Others would say everything has.

Flurries of gun-related legislation and renewed national attention on the topic have not been enough to change federal gun laws. The National Rifle Association, still the most powerful entity in the war over guns in America, no longer has a monopoly on the debate.

A resurgence of the gun control movement is challenging the status quo, while groups to the right of the NRA are also growing. Nonprofit organizations on each side are battling like they haven’t in years, all trying to shape the country’s politics and win over the American people.

But in spite of the evolving landscape, no progress in either direction is certain.

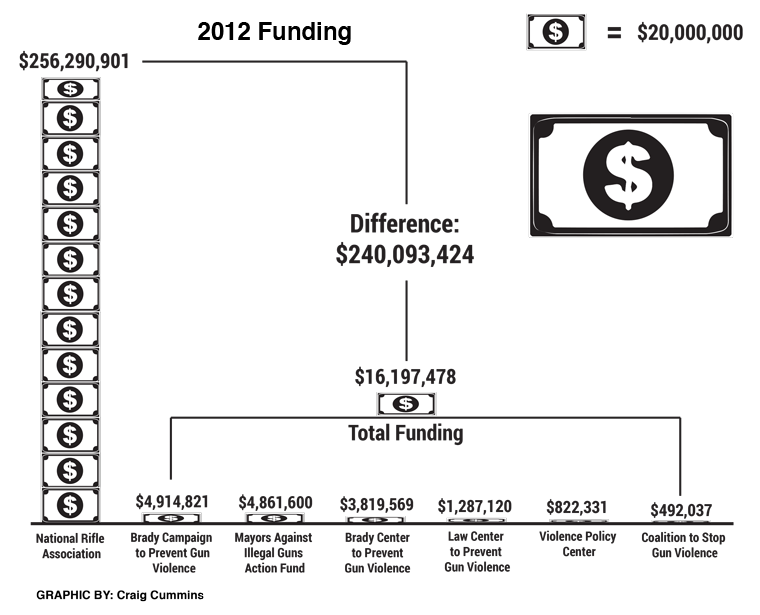

The gun control movement was nearly $285 million behind the gun rights movement in 2012 revenue raised, before Sandy Hook. Today, it is playing catch-up to the money, membership and political savvy of its opponents as the NRA works to maintain its dominance.

Over the course of this year, News21 reporters, videographers and photojournalists traveled across the country to assess the state of the gun debate, its evolution and emerging issues.

With new groups, a revamped strategy, more money and unprecedented collaboration, the gun control movement has made headway. Organizations like Everytown for Gun Safety, the group backed by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, say they are moving the needle.

“Now, for the first time in our country’s history, there is a well-financed and formidable force positioned to take on the Washington gun lobby,” said Shannon Watts, founder of gun control group Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, speaking at an Everytown event on Capitol Hill in May.

Whether that is possible remains to be seen.

The NRA is strong financially. Its budget has consistently hovered well above $200 million in revenue in recent years and it has cultivated a highly organized grassroots base for more than a century.

As the gun control movement organized in the wake of Sandy Hook, the gun rights movement’s membership boomed. Groups more conservative than the NRA, like the National Association for Gun Rights, are growing. State legislatures across the country passed laws expanding gun rights. The NRA has focused on broadening its appeal.

The NRA frequently targets Bloomberg, who donated $50 million to Everytown in April, though the amount is a quarter of what the NRA raises each year.

“Mr. Bloomberg, you’re an arrogant hypocrite,” said NRA Institute for Legislative Action Executive Director Chris Cox at the organization’s annual convention in April. “Stay out of our homes, stay out of our refrigerators and stay the hell out of our gun cabinets.”

With its near-mythical presence as a political lobby, the NRA is still the best-positioned player in the debate by far, bringing in and spending hundreds of millions of dollars on its broad range of programs. Though its grip on Congress has loosened somewhat, it still isn’t letting major federal legislation through or relinquishing its influence on state politics.

An amendment expanding background checks came to a vote in the Senate in April 2013, something gun control advocates saw as a victory. It didn’t get enough votes to pass.

The NRA began as a firearms education organization and sportsmen’s club in 1871 and didn’t become involved in politics until the 1970s. When it did, however, it had a built-in base of support. It has worked to build strong ties with members of Congress to back its lobbying and political efforts. Today, the NRA says it has 5 million members.

Around the same time the NRA entered politics, the group that would eventually become the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence was founded. It attained a high profile following the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan, in which Reagan press secretary James Brady was shot and partially paralyzed. Brady died this summer; his death has been ruled a homicide.

Its advocacy work in the ’80s and ’90s culminated in the passage of the Brady Act — which mandated federal background checks on people buying firearms — and the now-expired assault-weapons ban, both signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

In 1999, the Columbine High School shooting led to a resurgence of gun control advocacy. Like today’s movement, it had a billionaire benefactor in Monster.com’s Andrew J. McKelvey and a mother-led group, the Million Mom March. After a handful of state legislative victories, the movement fizzled.

This was the landscape when a spate of recent prominent mass shootings began: Virginia Tech in 2007; Tucson, Arizona, in 2011, in which former Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, an Arizona Democrat, was shot; the Aurora, Colorado, movie theater shooting in 2012; and then, Newtown.

The Sandy Hook shooting touched off for the gun control side what Everytown Director of Strategy and Partnerships Brina Milikowsky called a “once-in-a-generation moment of great transformation.”

The day after the shooting, Watts founded Moms Demand Action; a few weeks later, on the second anniversary of the Tucson shooting, Giffords and her husband, Mark Kelly, started Americans for Responsible Solutions.

In December 2013, Moms Demand Action formed a partnership with Mayors Against Illegal Guns, a group founded in 2006 by Bloomberg and former Boston Mayor Thomas Menino. In April, Everytown became an umbrella organization for the two other groups. Today, Everytown says it has 2 million members.

“Twenty years ago, Brady was the only game in town. And now there’s unprecedented resources and attention being focused on this issue, so we’re not a voice alone in the wilderness anymore,” said Dan Gross, president of the Brady Campaign.

In fact, there is a profusion of gun control groups, including many on the state level.

November’s congressional elections — the first major election since Sandy Hook — could provide a barometer for the political gun wars.

Some groups, like Moms Demand Action and the Brady Campaign, say they can now compete with the gun lobby. Others, like Giffords’ ARS, say they want to match the NRA but are still too new to have a comparable budget.

Gun control supporter Shannon Watts, founder of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, speaks at an Everytown event countering the National Rifle Association's annual convention in Indianapolis. Photo by Jacob Byk/News21.

With new strategies, groups like the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, founded in 1974, think they will “be a force for decades to come,” said Ladd Everitt, the group’s director of communications.

But tax filings show the top six national gun rights groups brought in close to $301 million in revenue in 2012, while six major national gun control nonprofits raised just more than $16 million.